Award-Winning Chicago Personal Injury Lawyer - Securing Justice

for Illinois Injury Victims - Over $450 Million Recovered

When a commercial truck fails to stop, it is rarely bad luck. It is bad maintenance. We expose the negligence behind ‘out of adjustment’ brakes.

CASE AT A GLANCE:

On the I-90/94 Dan Ryan Expressway, stop-and-go traffic places extreme thermal and mechanical stress on commercial truck braking systems. When an 80,000-pound tractor-trailer fails to stop in Chicago traffic, drivers almost always say the same thing: the brakes just did not work.

In reality, air brakes rarely fail without warning. When we investigate Chicago truck accidents involving brake failure, the evidence almost always points to negligent maintenance. The most common culprits are automatic slack adjusters that were never properly serviced and air systems contaminated with moisture. These are not unavoidable malfunctions. They are predictable, preventable failures that create clear liability for trucking companies and their maintenance contractors.

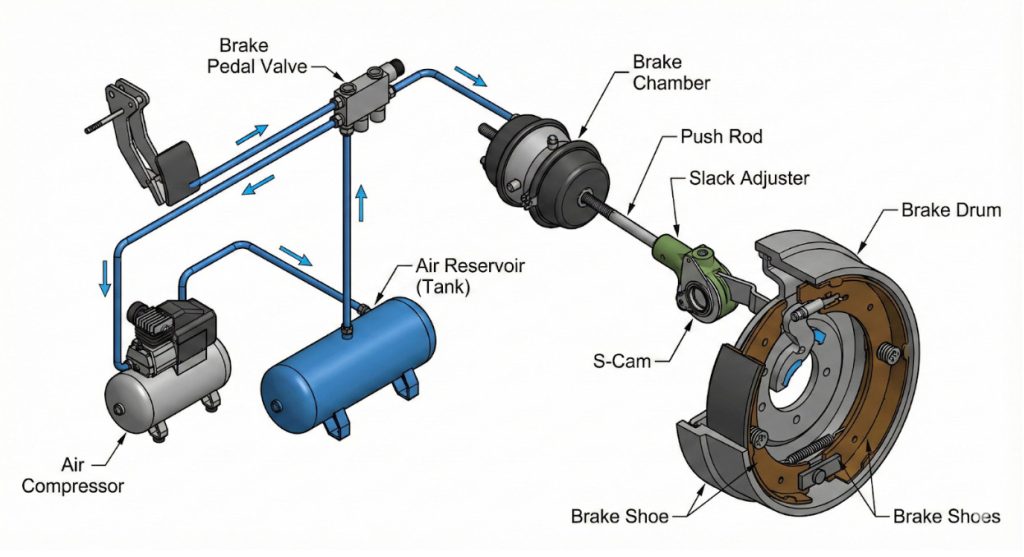

Fig 1.0: The anatomy of a commercial air brake system. Failure often occurs at the slack adjuster or push rod linkage, preventing the shoes from contacting the drum.

Commercial trucks do not use hydraulic brake fluid like passenger vehicles. They rely on compressed air to generate stopping force. Understanding that system explains why maintenance failures are so dangerous.

An engine-driven compressor pressurizes air and stores it in reservoirs. When the driver applies the brake pedal, air travels through pneumatic lines into the brake chamber. Inside the chamber, air pressure pushes a diaphragm that drives the push rod outward. That push rod rotates the S-cam, forcing the brake shoes outward against the inside of the brake drum. Friction between the shoes and the drum is what slows the vehicle.

Every part of that chain matters. If air pressure is restricted, contaminated, or delayed, braking force is reduced. If the mechanical linkage allows excessive movement before the shoes contact the drum, the brake provides little or no stopping power. When either failure occurs on a loaded semi-truck, the result is often a violent rear-end collision.

This is the failure we see most often in Chicago truck accident cases.

Automatic Slack Adjusters (ASAs) are designed to maintain the correct distance between the brake shoes and the drum as the shoes wear down. They function like a wrench incrementally tightening a bolt. Each brake application should advance the adjuster just enough to keep the stroke of the push rod within legal limits.

When slack adjusters are not lubricated or inspected, they seize. The push rod then has to travel farther and farther before the brake shoes make contact. Eventually, the stroke exceeds the legal maximum. At that point, the brake is effectively useless.

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) regulations are strict on this. Under 49 CFR § 396.25, only qualified brake inspectors are permitted to adjust these systems. Furthermore, under the “20 percent rule“, if 20 percent or more of a truck’s brakes are found to be out of adjustment, the vehicle is placed out of service immediately.

Certain air-brake failures appear repeatedly in Chicago truck crashes due to dense traffic, frequent stops, and seasonal weather conditions.

Chicago traffic conditions encourage drivers to ride their brakes in congestion. Continuous light braking overheats the brake shoes and drums, creating a smooth, glass-like surface known as glazing. Once glazed, the coefficient of friction drops sharply. Even with normal air pressure, the brakes cannot generate adequate stopping force.

Air systems naturally accumulate moisture. That is why trucks are equipped with air dryers that must be serviced regularly. When maintenance is ignored, water enters the air lines. In Chicago winters, that moisture freezes. Ice can block or delay the air signal to individual brake chambers, causing uneven or delayed braking.

Another dangerous practice we encounter is brake caging. When a brake chamber fails, some operators mechanically “cage” the spring brake to disable it and continue driving back to a terminal. This removes an entire brake from service. Operating a commercial truck with caged brakes on public roads is a violation of 49 CFR § 393.48 and creates immediate liability.

Investigating brake failure is not speculative. It is mechanical and measurable.

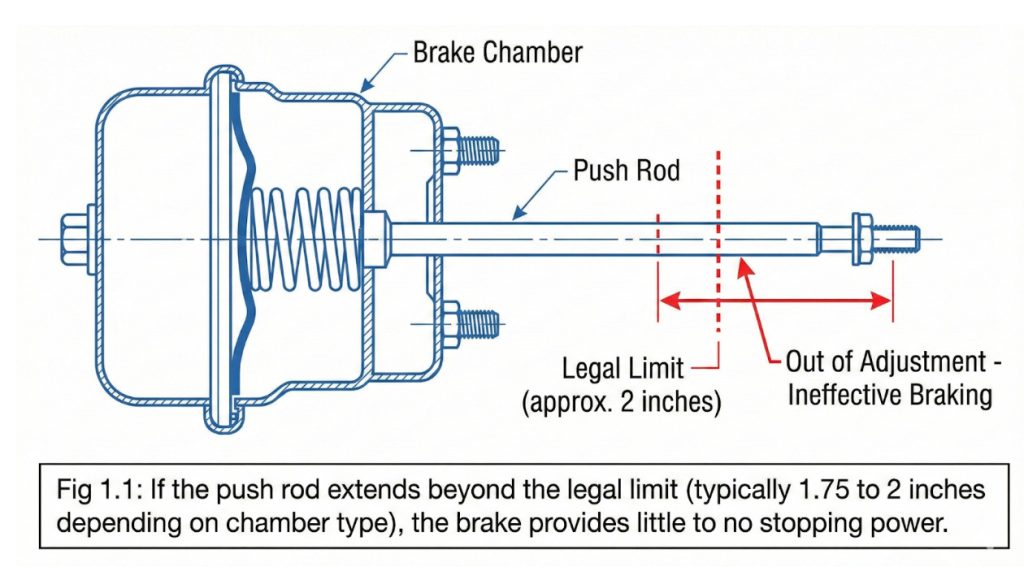

After a truck accident, our investigators measure push rod stroke on each brake assembly. Federal standards specify maximum allowable stroke lengths based on the type of brake chamber. For example, a Type 30 chamber generally becomes defective when the stroke exceeds approximately 2 inches.

All content undergoes thorough legal review by experienced attorneys, including Jonathan Rosenfeld. With 25 years of experience in personal injury law and over 100 years of combined legal expertise within our team, we ensure that every article is legally accurate, compliant, and reflects current legal standards.

Fig 1.1: If the push rod extends beyond the legal limit (typically 1.75 to 2 inches depending on chamber type), the brake provides little to no stopping power.

If we document excessive stroke after a crash, it demonstrates that the brake was out of adjustment before impact. Brakes do not suddenly slip out of adjustment at the moment of collision. This measurement often becomes the cornerstone of liability in rear-end truck accidents.

When a trucking company claims “sudden emergency” or blames the driver for “following too closely,” mechanical evidence is the rebuttal.

If you or a family member were injured in a collision where a truck failed to stop, do not accept “it was an accident.” Contact us to initiate a forensic mechanical investigation.

All content undergoes thorough legal review by experienced attorneys, including Jonathan Rosenfeld. With 25 years of experience in personal injury law and over 100 years of combined legal expertise within our team, we ensure that every article is legally accurate, compliant, and reflects current legal standards.